How much does YOUR club charge for a pie and a pint?

2020 has been a strange year for nearly every industry, but the future of English football has fallen under the spotlight as the true impact of the Covid-19 pandemic comes to light four months on from the UK officially entering lockdown.

Finance in football has been a rising concern for years, with much debate through the last decade of the ever-expanding margins between the Premier League and the English Football League’s lower divisions.

While the financial woes of former top-flight regulars Leeds United and Southampton saw both clubs slide into the third tier — League One — were well catalogued, it was Bury FC’s untimely demise in August 2019 that really brought the issue of football finance back to the fore just days before the current campaign commenced.

In this article, we will look at the impact of Covid-19 on the professional game, the threats to the future of clubs that have been around for over 100 years and the avenues of support available to clubs who find themselves on the brink of liquidation.

Football without fans

The coronavirus pandemic brought the UK economy to a halt back in March, and although most sectors are gradually returning – in some form – to a sense of normality, the consequences are only starting to rear their head now.

For football, one of the major challenges to restarting the season was an assurance that no fans would attend matches, keeping transmission rates to a minimum and ensuring health and safety measures could be maintained as far as practicable.

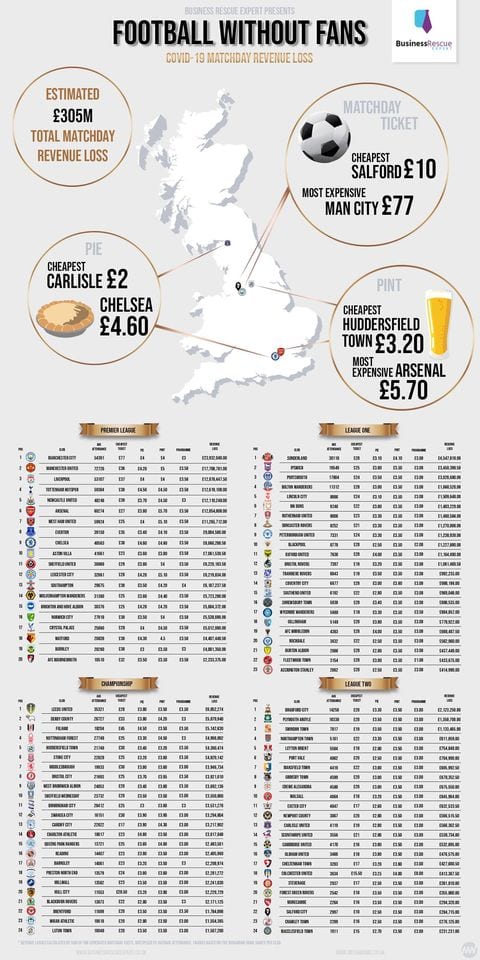

Taking the average attendances for clubs in the current campaign, where each fan enters with the cheapest ticket price and buys one pint, one pie, and one programme, we found that the 91 current clubs in the English league system would lose more than £305m — based on each club losing revenue from five home games until the end of the campaign. It’s a monumental loss, and that’s before you take into account broadcasting revenue, shirt sales, and corporate sponsorship.

It’s no surprise then to see famous names teetering on the brink of administration. Bradford City in League Two, when not bolstered by TV revenue, are set to lose £2,123,250, by closing their doors to fans.

The ever-widening financial margins between the Premier League and the EFL come into sharper focus when 2018/19 champions Manchester City are set to lose £23.9m. Even for one of the richest clubs in England, this is still 84 times more than near neighbours Salford City, whose estimated revenue loss sits at £284,715.

Tickets to the Etihad will always cost more than at Moor Lane but you can get in to watch Salford for just £10, while a trip to the Etihad Stadium will set you back at least £77 — that’s seven matches more than for one afternoon with Raheem Sterling and Sergio Aguero.

When you delve into the cost of season tickets, the disparities become even clearer. We hope they serve pints in golden goblets at the new Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, where the most expensive season ticket costs £1,995.

In contrast, the most expensive season ticket for League Two clubs came in at £750 which was at Northampton Town, whose fans will get to watch the likes of Sunderland and Ipswich Town next season after winning promotion to League One.

Covid-19 has stripped some of the simple pleasures away from life including the little things such as the joy of a pre-match pie and pint with mates.

The cheapest pies are to be found in their spiritual home of the North West, with Carlisle United fans tucking into their favourite cuisine for just £2, and Accrington Stanley, Blackpool, and Rochdale costing not much more at £2.50.

Less surprising is the fact that London clubs have the most expensive pies with Chelsea (£4.60), Tottenham Hotspur (£4.50), and Fulham (£4.50), making up the top three in this league.

A pint at Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium will burn a hole in your pocket at £5.70. For just 70p more you could buy two pints at Huddersfield Town, as they offer the cheapest pint for £3.20.

Surprisingly, Colchester United offer their matchday programme for free to loyal fans, but still face estimated losses of £413,000. Southampton have the most expensive programme, charging £4 to read their pre-match offering.

With the lost matchday revenue causing many a headache for clubs, a saving grace during the Covid-19 pandemic has been the benefit of the government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), which has enabled the clubs to furlough staff during the lockdown period in order to reduce costs.

However, the lost matchday revenue from seasons being cut short in Leagues One and Two and the Premier League and Championship being concluded without fans, means the true impact of the coronavirus on English football may not be seen for many months.

How did we get here?

When the Premier League was launched back in 1992, the idea behind it was for the country’s top players to benefit from a reduced calendar and give the national team a better chance of winning tournaments.

In reality, the main beneficiaries were the clubs who not only benefited from enhanced broadcasting revenue and TV rights, with Sky TV fresh on the scene to deliver pay-to-view matches but also being able to keep 100 per cent of their home match receipts for the first time.

Within ten years, the gap between Championship clubs — Division One as it was known at the time — had grown to such a point that parachute payments were introduced for clubs relegated to the second tier in order to mitigate the huge loss in income.

By 2004, points deductions were introduced for Premier League and EFL clubs entering administration — the process which sees creditors take control of the club to ensure that from its debts, wages owed to players and staff, and transfer fees owed to other clubs would be paid first — after some clubs were taking advantage of the process to clear debts while retaining their star players.

Wrexham became the first league club to be hit by the deductions, with 10 points being docked in December 2004, before higher-profile cases like Leeds United and Southampton followed suit a few years later.

Points deductions became the norm last summer as two North West clubs — Bolton Wanderers and Bury’s plights worsened. 27th August 2019 was a dark day for football when Bury were expelled from the Football League. The first team to suffer this fate during a season since Maidstone United in 1992.

Wigan’s woe spells out Covid-19 impact

With Bury FC expelled, the Football League was operating with 91 professional clubs when the Covid-19 lockdown cut the season short. Teams from Southend United to Macclesfield Town, and even Charlton Athletic in the Championship, had already been battling off-field complications regarding winding-up petitions owing to unpaid player wages, failure to fulfil fixtures, and controversial takeover plans.

Earlier this month, Wigan Athletic became the 20th club to enter administration since points deductions were introduced, with the club citing the coronavirus pandemic as having had a detrimental impact on finances.

A 12-point penalty was applied on 22nd July upon completion of the league campaign, and, although subject to an appeal from the club, the Latics were relegated to League One by two points, with Barnsley profiting from the North West outfit’s plight and escaping the drop.

Can we expect more of the same?

Wigan’s surprising trouble brings into sharp focus the difficulty of running football clubs, from the Premier League right down to League Two. Premier League clubs are facing a £1bn reduction in revenue because of the coronavirus crisis, so it comes as no surprise that the government’s Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) Committee has announced that it expected more clubs to follow Wigan into administration.

In a report on BBC Sport, committee chair Julian Knight said: “We know that 10 to 15 clubs could find themselves in the same position. (On Monday) the DCMS Committee sought clarification from (Premier League chief executive) Richard Masters on what action it was taking to provide extra money for clubs at risk — he told us that the Football League hadn’t asked for extra funding and the Premier League hadn’t provided it.”

As the league campaigns conclude, the DCMS went further by calling for parachute payments to become a thing of the past, a report stating that ‘the current football business model is not sustainable’.

During the last few months, the debate around the continuation of sport and its importance in society at a time when the health of the nation is on the line, has brought varied reactions. When Boris Johnson announced the return of sport at the beginning of June, he said it would ‘provide a much needed boost’ to the nation. Some sports fans would agree.

At a time like this, football is not just a game, it’s a livelihood — for players who might only get a 10-15 year career, for managers, for sponsors, and for all those staff working at the 91 professional clubs who all face an uncertain future.

While clubs have benefited from the CJRS and a £195m funding package from Sport England — which professional and community sports clubs can access — let’s hope teams across the country can weather the storm and line up for the start of the 2020/21 season — whenever it is and eventually with fans there to cheer them on as they have done for generations.